Note from Papanjari: What you’re about to read is not a typical interview. It’s a journey through time, memory, and creativity—told mostly in the words of Alexis Milant himself. We’ve made minimal edits for clarity, and just a sprinkle of seasoning to enhance the flow. All credit to Alexis for sharing such a rich and personal story.

PART 1 – The Early Days

PJ: What was life like for you growing up ?

I was born on November 22, 1972, in Limoges, a small French town with a population of about 100,000.

Between the ages of 9 and 10, I practiced windsurfing—my very first experience with board sports.

When I was 10, my father gave me a computer: a Sinclair ZX81. That’s when I discovered BASIC programming and fell in love with video games.

At the time, I dreamed of making them and turning that passion into a career—until a school guidance counselor, back in 1986, convinced me otherwise (to be fair, my academic performance had plummeted since my father passed away the year before). She told me: “There’s no future in that field anymore.” LOL.

Around that same time, I discovered role-playing games. A friend and I even started a club in our middle school. I created my own game: Ninja Warrior. I mean, What teenager wouldn’t want to play this game with a name like that ? ^^’

At that same age, alongside these more intellectual hobbies, I also loved diving—3 meters, 5 meters, 10 meters—no height scared me (that’s definitely changed now: I’m afraid of heights). But what I loved most of all was doing flips off the 3-meter board. My passion for flips probably started there.

PJ: When did skateboarding enter the picture ?

My passion for skateboarding developed in several stages.

When I was very young, in 1977, during a seaside vacation, I saw some adults skateboarding on a concrete path. That was my first shock.

Ten years later, during a summer holiday, I found an old blue plastic skateboard from the 1970s in a closet at one of my mother’s friends’ house. When we got back home, I saw some skateboards in a supermarket and asked my mother to buy me one. That summer, I skated every day, alone. I didn’t even know other people still did it. When school started again, I put the board away in a closet and forgot about it.

A year later, just before turning sixteen and right before summer, we were stopped at a red light in the car. On the sidewalk, I saw a skater standing still on his board. Surprised, I stared at him—I hadn’t seen a skater since the late ’70s. And then, the miracle happened: he crouched down, placed a hand on the nose of his board, then sprang up… and his skateboard lifted into the air.

Second shock—an overwhelming one. A kind of aesthetic, almost metaphysical slap in the face. Skaters didn’t just roll—they could fly!

I went home, pulled my board out of the closet, and tried to do an ollie. A week later, I managed to jump over a small stick on the ground without touching it. What pride! I could fly too.

PJ: Did you have a crew you skated with—or were you more of a solo explorer?

A few months after landing my first ollie, I joined a group of skaters in a square in downtown Limoges—Place d’Aine—but only after I had landed my first kickflip. That was the sine qua non condition I had set for myself: there was no way I was going to join those pros and look like a beginner!

So it was with my ollie and my flip in hand that my group adventure began. What a joy, what a sense of freedom!

PJ: Outside of skating—were you already drawn to creative stuff like filming, editing, drawing, storytelling?

As I mentioned earlier with windsurfing, that’s actually where I unknowingly achieved my first real feat in board sports: I didn’t fall into the water for several months after starting. I didn’t want my father—who also windsurfed—to see me fall, just in case, for once, he happened to look at me. He was distant, emotionally absent, and never gave compliments.

Yes, I learned to sail without falling! One of my proudest achievements… though with a bitter aftertaste.

Alongside video games and role-playing games, I also played the guitar and loved to sing.

By 1991, I had become a good skater from Limoges.

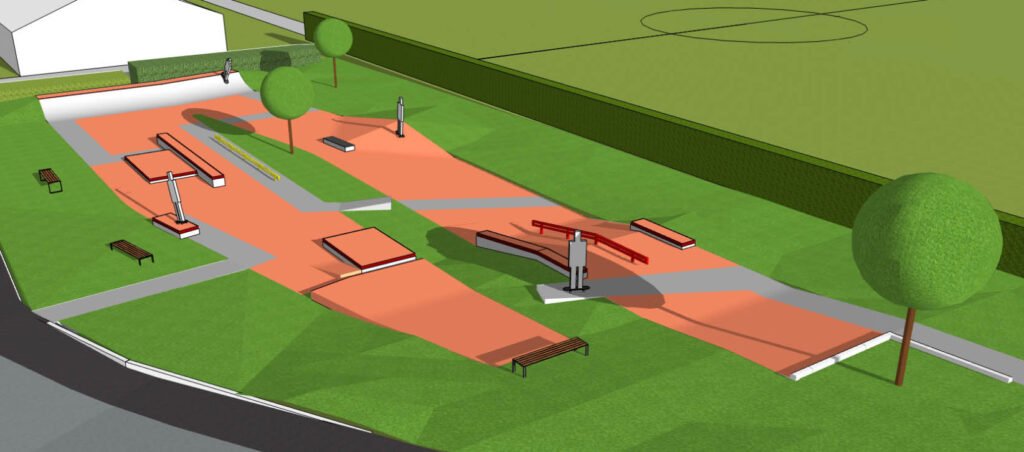

That’s probably why a guy my age, whom I didn’t know, came up to me and said his mother worked at city hall, and the city was planning to build a skatepark. He asked if I wanted to design it. What an opportunity!

With a friend, we had fallen in love with street skating, a discipline that was just beginning to emerge, and we designed an all-concrete skatepark with stairs, handrails, ledges, curbs… We called it a streetpark. It was built in 1992.

To this day, I’ve never heard of a skateplaza built before that. At the time, in the U.S., most skateparks were made of wood—mainly for insurance reasons—and were inspired by ocean culture, all curves and flow. Even street areas were made up of curved obstacles: funboxes, small quarters, mini spines, and so on.

So it’s quite possible that in 1990, with my friend Mickaël Cadet—who chose to name the park Place Mark Gonzales—we designed the world’s very first skateplaza. That remains, to this day, my greatest pride.

We didn’t invent anything. We were just there, in the right place, at the right time.

So it’s quite possible that in 1990, with my friend Mickaël Cadet—who chose to name the park Place Mark Gonzales—we designed the world’s very first skateplaza. That remains, to this day, my greatest pride.

PJ: And eventually, how did fingerboarding show up in your life? Was it love at first sight, or something that grew over time?

I was studying architecture in the city of Bordeaux. I must have been around 20 when I came across a Tech Deck keychain. I removed the metal ring that went through a small hole near the nose, and with a few skater friends, we played with it from time to time on rainy days—never realizing that an actual practice was starting to emerge.

To be honest, that little object annoyed me: landing a flip seemed impossible. Was it even possible to control anything at all? I seriously doubted it…

Then, when I stopped skateboarding around the age of 22—for a period of ten years—I put the keychain away in a drawer.

PJ: Looking back, do you remember the moment when you thought: “Wait, I want to film this… and make something out of it”?

I was 32. I had just left Paris to return to the small town where I was born. I had quit my job as a sound and lighting technician for live shows, and I wanted to become an artist. But what could I do?

I had a camera… and I opened that drawer. That’s when the idea came to me.

I wasn’t skateboarding anymore, but I wanted to share the passion I had once for it—especially the joy you feel when you land a trick.

I told myself: “I may not be able to skate anymore, but I can stage this miniature skateboard with the objects around me, as if I were filming my memories, my inner world, in order to convey the emotional intensity that skateboarding—and its relationship with urban architecture—once gave me.”

PART 2 – The Creation of OPUS 0

PJ: Let’s start with the name—why “OPUS”?

I found the name after finishing the video edit. Unable to come up with anything that felt right—and wanting to affirm that I had become an artist—I thought of the word opus, a Latin term (a dead language that gave birth to many French words) which can mean “work,” “piece,” or “composition.”

The choice came naturally, both for its simplicity and, I must admit, as a kind of social signal—a mark of distinction. By using a Latin word, I was trying to capture a bit of the aura of great musical artists.

PJ: The video doesn’t feel like “just” a fingerboard edit. It has flow, atmosphere, a beginning and an end.Did you storyboard or plan certain sections—or was it more spontaneous and experimental? I can’t recall any fingerboard video like this in the early days I found fingerboarding online. Most of them just table top fingerboarding at best.

After my architecture studies—which lasted only one year—I spent two years studying visual arts, where I learned to think through and structure my work.

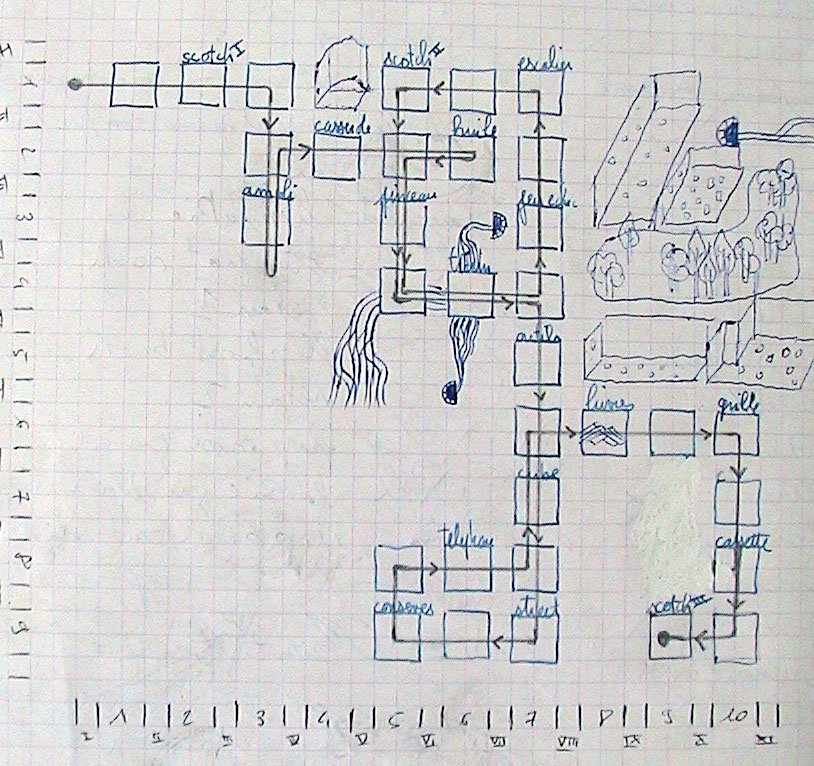

So before I started filming, I did some preparatory work: drawings, written intentions, video tests, and a storyboard.

I first imagined the video as a journey, as if my hand were moving through an imaginary city.

From that diagram, I was able to deduce not only all the shots—including transitions—but also the direction from which my hand would enter and exit the frame in each one.

For each scene, I had jotted down a minimal note about the setting: toaster, oil, saucepan, etc.,

leaving myself room to improvise the final composition during shooting.

What’s crazy is that, at the time I made the video, I thought I was the only person doing fingerboarding. I had no idea that a scene was beginning to emerge, and I didn’t even know about YouTube, which had just launched.

Since I wasn’t following any existing conventions, I was free to define my own way of filming fingerboarding.

I first chose top lighting and plunged the room into darkness so that my body would disappear—except for my hand, giving it the status of a character in its own right.

I also decided to perform tricks as realistically as possible, with the intention of imitating actual skateboarding, as if it were just a change of scale.

But most importantly—and I believe this is what had the biggest impact—I shot every trick in slow motion, so the viewer could clearly see the movement of the board.

As for the intro and conclusion, I wanted to create a loop: to bring the video into a different universe, then bring it back out again.

Hence the keychain that, for a moment, becomes a fingerboard. The hand, too, is caught in a loop: it starts by jumping over a “motorbike,” and ends up crashing and “dying” because of that same object—so that the fingerboard can return to being a keychain.

Isn’t life a loop?

And now… I have to confess something. But only if you promise not to tell anyone: I cheated!

At the beginning of filming, I had absolutely no idea how to fingerboard. But I discovered that by covering the board with tape, the inner edge—the one facing me—would stick just enough to my index finger so that when I did an ollie, the board would “automatically” perform a heelflip.

That’s why there are no kickflips in the video—only heelflips!

But even with this “hack,” each shot took me between one and two hours of filming—roughly 500 to 1,000 attempts per trick… It was a true test of patience.

My nerves were pushed to the limit… But shhh, that’s a secret!

PJ: You mentioned showing early sketches in the remastered version—can you talk more about what those were?

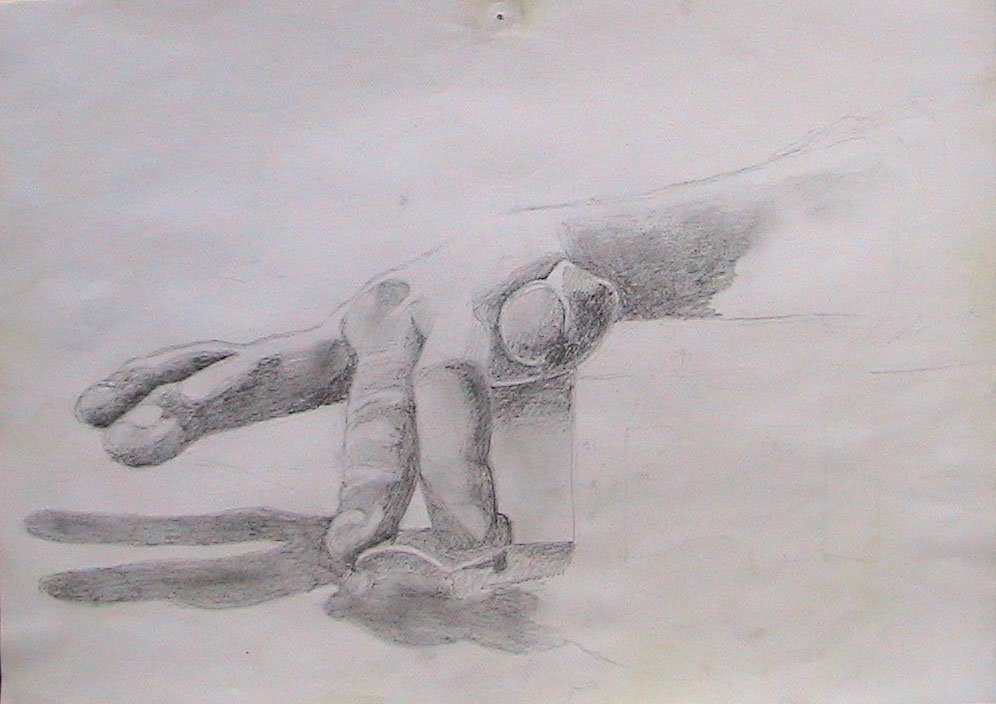

At that time, I felt the need to draw—perhaps as a way to pay tribute to my mother, a painter who had passed away five years earlier, and probably also to prove to myself that I, too, was capable of creating some worthwhile drawings.

The preparation for this video gave me the urge to make around fifty of them (not all of them are good), in both black and white and color.

PJ: The intro, music choices, and pacing all add a sort of ‘short film’ feeling. Were you inspired by any filmmakers, musicians, or visual artists at the time?

Yes, with Opus 0, I wanted to create something that sits somewhere between a short film and a video art piece. In fact, a few years later, it was screened in Paris at the Centre Pompidou (Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou).

Inspired? I don’t know. Influenced? Definitely.

Like everyone, I suppose: Charlie Chaplin, Akira Kurosawa, Stanley Kubrick, and many others…

The intro music, chosen to evoke a dreamlike, parallel world, was taken from two films: Eyes Wide Shut by Stanley Kubrick and Akira by Katsuhiro Otomo.

At that time, I mostly listened to rap. Back in 1990 and 1991, I used to rap in a group called Le Substrat. I still write lyrics from time to time.

I also listened to techno—hardtek, tribe, breakbeat, drum & bass—even though I’ve always had a soft spot for Georges Brassens, the beloved French singer-songwriter.

As for video artists, I really admire Pierrick Sorin, Tony Oursler, and Fischli & Weiss.

PJ: What tools did you use for filming and editing?

A small DV camcorder in 576i for filming, and Adobe Premiere Pro for editing. Later on, I used Adobe After Effects for the slow motion in my skateboarding videos.

PJ: Looking at Opus 0 now, does it still feel like “you”? Or do you see it more like a snapshot of who you were back then?

Yes, it’s still me: a cheerful depressive, caught between shadow and light, burdened yet also sheltered by a creative solitude.

When the trap of reality closes in, when sunny days give way to rain, I retreat into an inner world—where skateboards shrink, but emotions grow immense.

PART 3 – Reflections & Legacy

PJ: How was the fingerboard scene around you at the time of Opus 0 or prior to that? Opus was released 2006, and based on my chat with Damien from Close Up, it was the time where it actually start growing in France or Europe.Were there other people filming, jamming, or pushing the same kind of ideas—or were you kind of isolated in your own lane?

I didn’t know that fingerboarding was becoming a real practice, a culture. I wasn’t even skateboarding anymore at that time. ‘Isolated’ is the right word — on my little desert island, with my keychain and my camera.

PJ: Did you ever imagine that Opus 0 would be talked about this many years later?How do you feel knowing people still reference it, globally?

Of course not. I had organized a little video night at my place and invited about fifteen friends to show them what I had created. At the time, I thought they would be the only ones to ever see it.A few days later, a friend told me about YouTube. He had an account, and I immediately uploaded my video there. He eventually gave me the account, which is why it’s called 11matt—his name was Mathieu.

To answer your second question: yes, I’m very proud of it. Proud like a rooster crowing at dawn (the rooster being the national symbol of France).

But what moved me the most were the comments under the video, which I only started reading recently—probably out of fear of finding negative feedback, something totally incompatible with my melancholic nature and recurring bouts of depression.

And then, I was blown away: people were praising me. I even broke down in tears when I read one comment in particular. It was from a man who said that, as a child, after discovering fingerboarding thanks to my video, he had shared special bonding moments with his father.

I had helped a child experience joyful moments with his dad—something I had always dreamed of having with mine.

PJ: We’ve seen a lot of influence from the US and Germany in fingerboard history—but France had its own vibe.What do you think made the French fingerboard scene unique back then?

Very hard to say… Maybe sociologists or anthropologists would have an answer.

What’s certain is that France has a deep admiration for American popular culture : its literature, cinema, sports, painting, and of course music.

It’s also worth noting that artistic production in France during the 20th century was especially rich.Maybe it’s for those two reasons that Damien (Close up) and I embraced North American culture, with a more artistic approach than in some other European countries.

But that’s far from certain.

PJ: That Hermès videos you did—how did that project come about?It’s wild to see fingerboarding go from bedroom edits to a luxury fashion campaign. Did they find you because of Opus 0? What was the experience like working with a brand like that?And was the money good?

It was a company called Ampm, which worked exclusively for Hermès and handled the brand’s communication on social media, that reached out to me. It was actually the 12- to 14-year-old son of the couple who ran the company who told them about my video Opus 0.

Yes—it was thanks to a child that I got to work with Hermès twice!

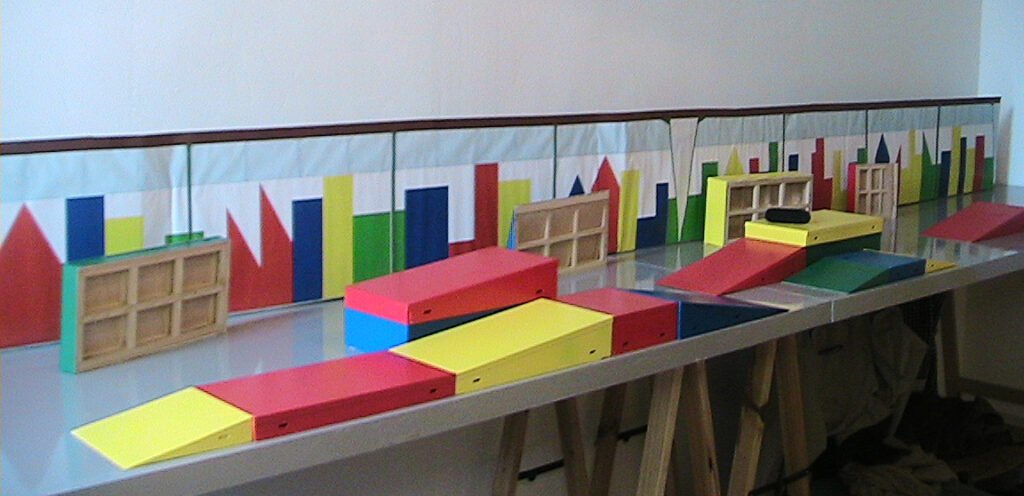

It was a very pleasant experience: every time I made a request, they replied with a simple “okay.”That’s how I got the chance to meet and work with Elias Assmuth and Dimitri Schlotthauer, to have custom lacquered wooden modules made that could be assembled into as many skate spots as needed, to work with an HD camera, and to have everything I needed delivered to me.

Their first commission was a video : I was paid €4,500

The second project involved a video as well as the scenography of an entire room.

It was a showroom event organized to present a new collection to Hermès’ resellers.

The room featured a huge table over 10 meters long, on which I had set up all the wooden modules, mixed in with various Hermès products, creating a giant fingerskatepark.

The audience could watch Elias and Dimitri perform tricks live while the video played on a large screen behind them. At the end of the demonstration, everyone applauded—a true success!

I earned €8,750 for that job

PJ: Do you still keep up with fingerboarding today? Either casually, through people you know, or just watching from a distance?

Yes, I still do a bit from time to time, using the old fingerboard Elias gave me when we first met. Sometimes I practice alone, but often with a friend who’s much better equipped than I am—with the latest decks, trucks, and wheels from various brands.

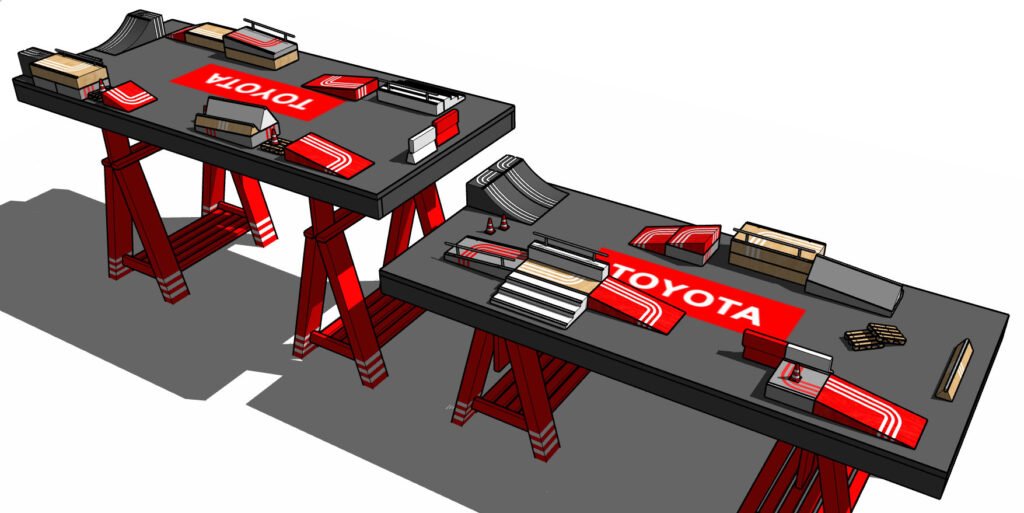

I recently built myself a fingerskatepark with about fifteen wooden modules, which can be assembled like LEGO bricks to create as many spots as you want. It’s actually a miniature replica of a skatepark I designed two years ago for a competition held in the city where I live.

I briefly considered selling them, but the time it took to build each one quickly discouraged me. At around €50 per module, they would’ve been far too expensive—basically a luxury product, unless I had them mass-produced far from France… but I’m not an entrepreneur.

If someone in Indonesia is interested in taking on the whole production and sales process, they’re welcome to reach out, haha.

Aside from the fingerskatepark I just mentioned, I also designed one for Toyota during the Olympic Games.

Right now, I’m designing concrete skateparks and wooden ones as well.

I still write a few rap lyrics now and then. I also create posters from time to time by cutting and gluing together colored A3 sheets by hand.

I also enjoy philosophy, and for many years I’ve been developing a moral theory conceived as a kind of transcendent force.

This force would lie at the origin—and at the heart—of how life organizes itself, including in animal (human) societies.

It would be something like a gravitational social law : a dynamic that compels individuals to emit and receive signs encoded with exchangeable values, thereby creating bonds and forming a network—a society.

At the center of this process, I identify a deeply entangled need for imitation and distinction. The values produced by Homo sapiens sapiens would, in this view, depend on feelings of shame and pride—emotions linked to the degree of identification individuals have with their role models.It’s a long-term epistemological project that may never be fully completed, but one I feel compelled to pursue—driven by my desire for truth, a desire born from an injustice I experienced as a teenager : the death of my father… but I’m getting a bit off track.

To answer your final question: yes, I recently got back into skateboarding after two consecutive fractures, one of which was a femur break fixed with a 20 cm nail.

And yes, I’m planning to produce new videos soon that combine skateboarding and fingerboarding—with the idea of performing the same tricks using both the big and the small board.

PJ: And if you had to describe what fingerboarding gave you—what would that be?

Recognition, connections, work opportunities.But above all—pleasure: finally landing your first tre nose manual or your first flip back tail after thousands of attempts—pure bliss! Like an orgasm!

PJ: Last one: when someone new finds Opus 0 for the first time—what do you hope they feel? Or take away from it?

I hope that, like you, they’ll make the video their own—that they’ll see something in it I hadn’t noticed, that it will make them want to watch it again, to pick up fingerboarding, and who knows…

maybe even interview me in twenty years